A version of this essay was first published by Nesta as part of their Rethinking Parks essay collection.

This essay explores the physiological impact of cityscapes and how environmental city stressors, in the absence of nature, create a habitat which can trigger chronic stress and traumatise.

During the Covid-19 outbreak, our need for nature to support resilience has demonstrated that wildlife habitats, parks, green and blue spaces, are essential assets and not luxuries. It has also revealed that millions of us don’t have easy access to green spaces within walking distance and that there are socio-economic and racial disparities in accessing nature’s health benefits in cities.

Ethnic minorities died of Covid-19 at a greater rate. Evidence suggests that part of this is because the Covid-19 mortality rate was made worse by air pollution and ethnic minorities and people on lower incomes tend to live in areas with greater air pollution. Green space and trees counter air pollution, however, ethnic minorities and people on lower incomes tend to live in areas with fewer trees and less access to green space. In addition, it was harder for lower paid essential workers to avoid social contact than higher earning employees who could shelter at home. The pandemic also revealed that those with money and means could relocate to greener areas, whilst those without were trapped within the city’s stressors. Making cities greener is a crucial public health response to an environment that doesn’t currently meet our needs.

Urban areas are home to over 83% of the UK population. It’s where we live, work and play, yet seemingly cities have been designed with an acceptance of environmental stressors which harm health – rather than designed to nurture and support health, qualities associated with nature, our natural habitat.

The city environment and its stressors (air pollution, noise pollution, visual pollution) have a detrimental effect on our cardiovascular system, neuropsychiatry, and gastrointestinal, reproductive, respiratory and immune systems. This leads to an increase in disorders such as male and female infertility, miscarriage, fetal development issues, low birth weight, Alzhemers, Parkinsons, high cholesterol and early death from asthma, lung disease, obesity, diabetes, stroke, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

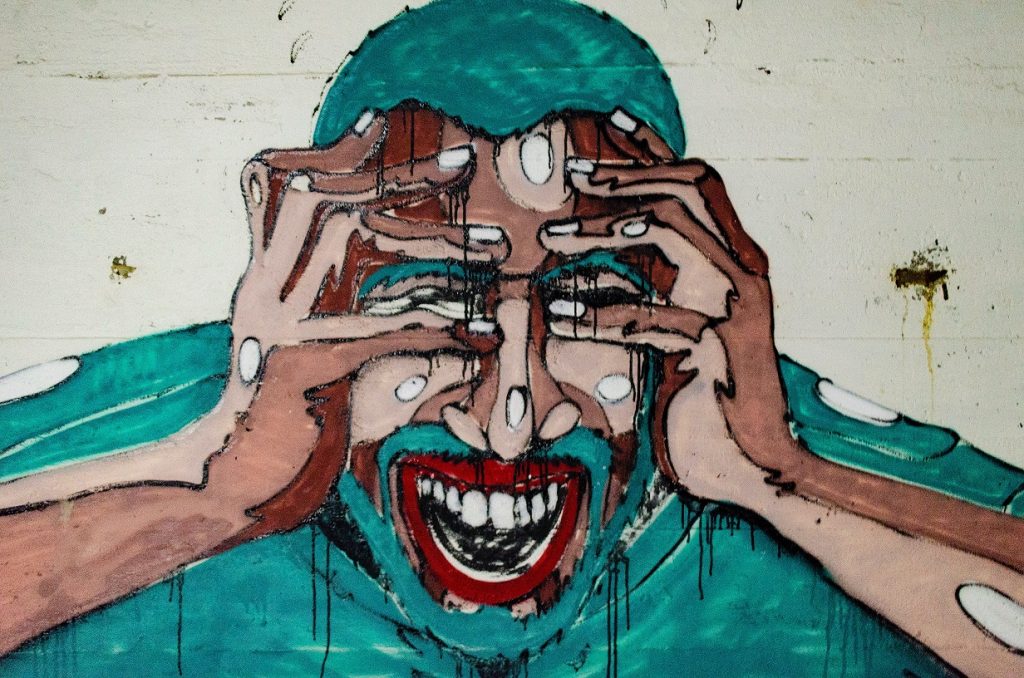

Loud noise, hectic movement of people, traffic and other competing visual stimuli of signs and lights take a toll on our autonomic nervous system and can be experienced as overload which our bodies perceive as a threat. This, in turn, triggers our fight, flight, freeze response, designed to protect us from danger. It is a survival instinct. When exposed to ongoing stressors that put us on alert for an extended period of time, we are likely to become irritable, angry, anxious or depressed and experience fatigue or burn out. Ongoing relentless stress from situations that leave us feeling overwhelmed and isolated can lead to emotional trauma.

Non-polluted natural environments, in contrast, can lower stress and heart rate, calm our nervous systems and support optimum health. Contact with nature can support us through hard times and help us to recover and repair from the inflammation of stress by inducing feelings of relaxation and connection.

Contrasts between living and survival

The impact of being in an urban environment evokes the same feelings as being in a psychological state of ‘survival,’ with high levels of the stress hormone cortisol and a high heart rate, operating more in adrenaline with a lower quality of rest and sleeping problems. It can also lead to emotional detachment, withdrawal, feelings of being overwhelmed, anxious and isolated, or becoming more aggressive and combative.

Being in a natural environment correlates with the feelings of being in a psychological a state where we are ‘living,’ with a lower heart rate, lower cortisol levels, feeling rested, relaxed and having a sense of belonging. In nature it is much easier to be in the moment with our feelings and have a general sense of well-being.

We are more adrenalised in the city, away from nature. We’re not meant to live on constant alert, survival mode is meant to help us cope with occasional encounters and not to be our default.

Optimum habitat

Humans are not outside nature but part of nature. As such, we are vulnerable to habitat change just as the hedgehog and the stickleback. We have needs and requirements from nature in order to live in health and we suffer poor health when our environment does not provide optimum conditions. Wildlife and humans feel stressed when our natural habitats are tampered with, urban residents with a deficiency of access to nature are impacted most.

Our evolutionary biology hasn’t quite caught up with the environments that we’ve created for ourselves. Our physiological systems are designed for regulation by circadian rhythms which in turn are imprinted into the phenological rhythms of nature, and the effects of nature performing her natural cycles and interactions.

We have lost touch with the baseline for what’s normal in terms of biodiverse habitat health. We tend to base our view of normality on what the norm was during our formative years. We do the same for our baseline of city stressors. If we grew up with pollution, sensory overload and deprivations we tend to see that as normal and it becomes our baseline for accepting stress and accepting the traumatic response.

There’s a danger that our baseline for natural habitats and our baseline for city stressors have become normalised at an unhealthy level. ‘It’s normal to have few birds, it’s normal to have loud noise’. We seem unaware of what we’ve lost, with each unhealthy city element we pile up layers of disconnect and trauma; removing nature, introducing air pollution, noise pollution and fast traffic.

Dysfunctional relationship

There is a strange denial that we’re not directly affected by habitat loss, rather we externalise it as a matter of stress and loss to ‘other’ species, and not to ourselves. We have a delusion that as humans we are above needing nature for our own sakes. As a habitat, we ‘cope’ with they city but haven’t yet ‘adapted’ to it – this is evident from the stress signals it activates in us, and which we are primed to ignore. Our quality of life would be higher with more nature. Why don’t we bring more in?

We have a dysfunctional relationship with the city, it harms us but we still tolerate it, as if we didn’t have a choice to change it. We need to break the trauma bond of our dysfunctional relationship with an abusive environment and let go of systems and norms which bring the comfort of familiarity but which are causing us harm.

De-traumatising the city

We’ve been here before, toxifying our cities in the name of progress. The mid 1800’s saw a number of outbreaks of disease related to larger numbers of people living in industrialised cities and environmental stressors which harmed the public’s health, triggering change. The cholera outbreak of 1832 and the Great Stink of 1858 showed a lack of sanitation was harming human health; infrastructure did not meet the needs of the populace.

Motivated by an outbreak of typhoid in 1838, social reformer Edwin Chadwick’s investigation into urban sanitation explored how the city’s design led to negative health outcomes and the spread of disease. His response was to effect social justice for the ‘labouring population of Great Britain,’ recommending improved drainage, clean water and removal of waste in addition to government pensions, a shorter work day and a transfer of funds from prisons to preventative policing – not so dissimilar to calls for social and environmental justice today.

We are also at a time of reckoning, in a year we couldn’t breathe. Sanitation and disease in our era is not just viral and bacterial outbreaks but pollutants and stress.

De-traumatising the city means implementing environmental justice and allowing more space for nature as a health necessity for all, not just the moneyed and privileged. We know that people who live closer to green spaces live longer and are less stressed. We know that people in areas of deficiency of access to green space also experience higher levels of air pollution, and areas with fewer trees experience more crime and hotter summers. So why are we not addressing these disparities as a public health issue?

In the same way the State provides everyone with sanitation as a basic of health, everyone should be provided with nature sufficient to mitigate city stressors. Nature contact is a life lengthening, health supporting essential, not a luxury. We need to do more than make streets look pretty with flower boxes. We need to be brave and create enough nature sites in neighbourhoods as needed to recover our health. Nature’s recovery and our own are intertwined.

Air pollution is no more a necessary evil that open sewers were in the 1800’s – there may be a period of change or temporary inconvenience to achieve a better life for us and future generations. We should be glad that Victorian Londoners accepted this inconvenience so that we are no longer troubled by stink and cholera.

Increasing wildlife sites will offer some respite; soft ground, tree leaves and bark absorb sound waves, dulling the abrasive impact of loud noise, lessening the impact of sound on our nervous system. They will also cool our cities and absorb pollutants.

But rather than conceiving parks as boundaried spaces within a city, we need to think of the city as a habitat and consider whether it is fit for a human, and be concerned with the quality of the air we breath, the noises we hear and the state of ‘living’ we are able to achieve within it. The city is our zoo, if we must be removed entirely from a fully natural habitat, as much as possible needs to be brought in to make it habitable without us becoming depressed or enraged.